Precious Blue The most interesting paint on my palette

Aside from the clear sky, there are comparatively few things in nature that are colored blue – even an apparently blue body of water is just a reflection of the sky (and the sky isn’t really blue either – what we see is the black of deep space through the haze of Earth’s atmosphere, colored by some nifty tricks of light scattering).

It’s the rarest color in nature.

In fact, compared to yellow, green, or red, almost nothing is blue – I could only think of a few birds and fish, some flowers, a couple of stones.

That rarity makes it all the more special, particularly where paint is concerned.

Until the modern age, blue was the problem color for artists – there just were not great sources of the color that were clear, intense, and permanent – and could be made into paint.

The exception was Lapis Lazuli.

Lapis is a remarkably intense, beautiful, deep rich blue stone which has endless uses in the decorative arts and jewelry.

Its beauty was no doubt enhanced by its rarity – it’s a semi-precious stone that until recently was only found in one place; Afghanistan.

As a luxury item in high demand, it was traded widely along the Silk Road and similar networks.

It appeared throughout the ancient world – notably in the famous funerary mask of Tutankhamun from the 12th century BC (above).

As the art of painting developed in Europe during the Middle Ages, artists were confronted with the lack of a good blue.

A few blues were available from plant sources (notably Woad and Indigo) and several minerals (Azurite), but none of these made a great paint – most often they were weak and anemic in color and slanted towards green, and often faded quickly.

But not paint made from Lapis Lazuli.

Starting in about the 13th century, artists began to understand the process to make paint from Lapis, and they then had the most stunningly beautiful blue to work with, as seen in the below example from about 1395 – deep, rich, clear, pure blue.

But it was still not easy, or cheap… in fact quite the opposite.

Many paints on the artist’s palette come from ground stones and clays, and are made by the simplest process: Take your stone, grind it to powder, add a little oil, and begin to paint.

Sadly this doesn’t work with Lapis.

Even the finest grades have high amounts of impurities – the calcite and pyrite that give stones of Lapis their beautiful golden veins.

Although a stone of Lapis might appear deep blue, when ground into a powder, these impurities cause the powder to appear bluish-grey, rather than the rich pure blue in native stone form.

So, the impurities must be removed – a lengthy process that involved folding the powder into a mixture of natural waxes and resins, forming the paste into small sticks that fit in the palm of the hand (think a baby carrot), and then holding these sticks in a mixture of lye and water and kneading them manually for hours.

Through this process, the blue would tint the liquid itself while most (but not all) of the impurities remained in the paste. The water would then be evaporated off, leaving a relatively clean pigment which could be made into paint.

Needless to say, this made it very, very expensive.

Not only did the stone have to travel thousands of miles across a treacherous trading network, but it then had to be extensively processed before it could be made into paint.

I had a hard time finding specific numbers, but a few references state that paint made from Lapis was several times more expensive by weight than gold.

And this exotic pigment came to have an equally evocative name – Ultramarine – Latin for “across the sea”, reinforcing its mysterious and other-worldly origin and nature.

So it continued for centuries – Ultramarine was the premier blue pigment that artists had access to when they (and their patrons) were willing to pay a premier price for it.

In 1826, a process was discovered to produce a synthetic equivalent that was identical to Lapis Lazuli, both chemically and visually.

This made the pigment about 1/1000 the cost of Ultramarine made from ground Lapis, and was far purer and more beautiful as well.

Almost immediately, this became the blue of choice for artists – synthetic Ultramarine is now one of the cheapest pigments available, and graces nearly every artist’s palette.

Modern chemistry has wrought miracles for the artist, and there is now an astonishing range of blues available to us – I counted 11 different blue paints in my studio, and there are a number of blues that I have never purchased and tried.

And yet, Ultramarine paint made from genuine Lapis Lazuli is still available.

Lapis is slightly more common now (in the last century, a few small deposits were found in Chile and Colorado), and the processing into paint is done by machine, of course. It’s still expensive, but nowhere near the cost of gold – maybe between 5 and 10 times the cost of the synthetic Ultramarine paint.

About a dozen years ago, I bought a tube of it out of curiosity (I think I paid $50 for it, whereas a tube of synthetic Ultramarine can usually be had for $8).

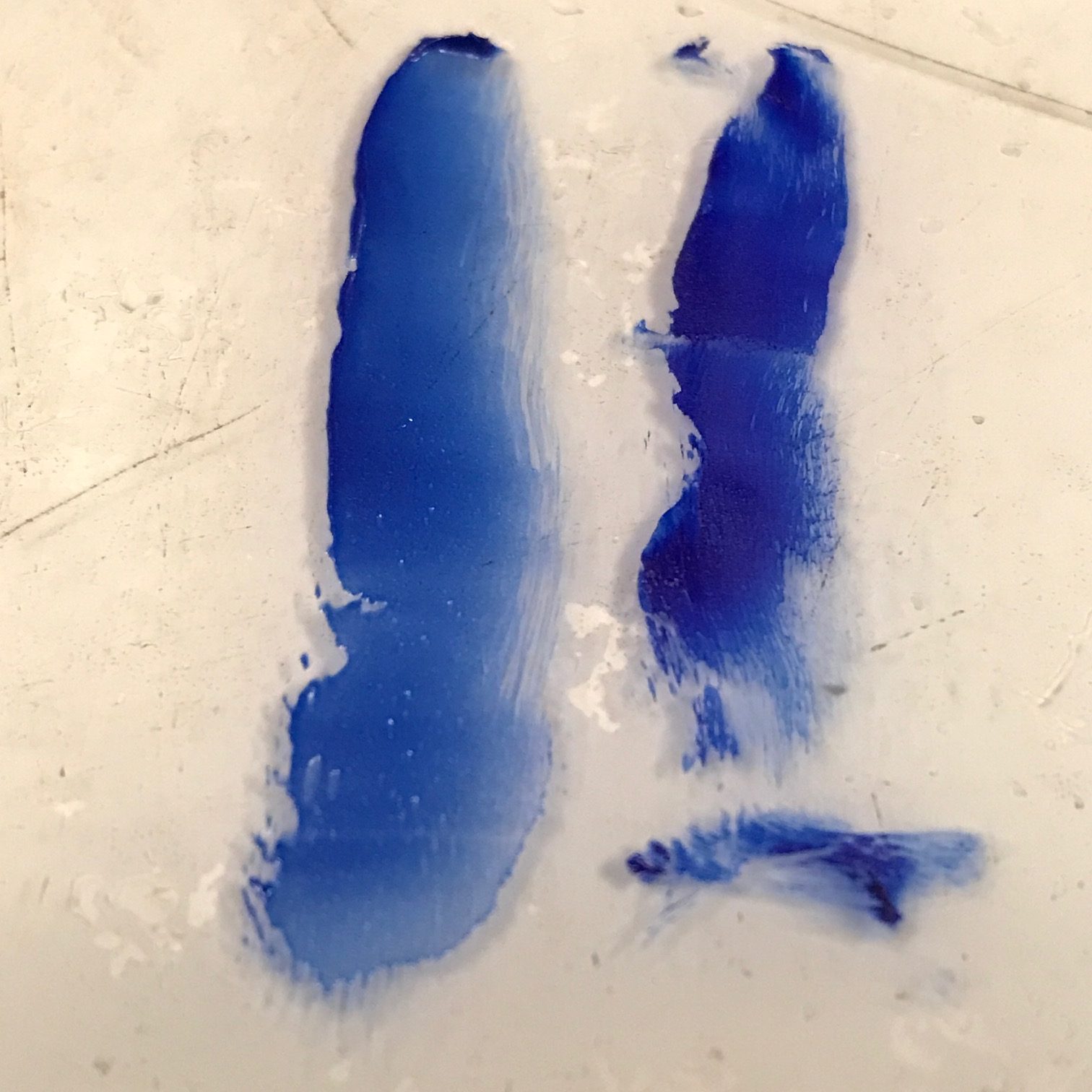

Far from being the resplendently beautiful paint I was expecting, it was a real disappointment – dirty, grey, and nowhere near the clean purity of the cheap synthetic blue right next to it (it was likely made from low-quality stone or was not properly processed to remove impurities).

I thought to myself “well that stinks” (in stronger language) and put it in storage along with other paints I rarely use.

And yet, it has had a surprising second life in my studio – not as a blue… but as a grey.

Artists almost never use paint directly from the tube – it is usually too strong and saturated, so they must mix in other colors to tamp this intensity down – to “grey it”, as we say.

This is often done by mixing in a little bit of the color that is opposite on the color wheel – the complementary color.

For instance, red can be made a little greyer by mixing in a tiny bit of green.

The synthetic ultramarine can be used for this, but as a strong, saturated pigment, it is very easy to overshoot the mark and add too much blue.

But, a few years ago, I realized that this unused tube of genuine Lapis Lazuli might be good for greying down other colors, and so I tried it, and discovered it was perfect for that role.

And so, this magic pigment with such a storied past now fulfills the humblest role on my palette – making other colors greyer.

At least my $50 was not completely spent in vain.