Ruggiero Ricci Recollections of my time spent with a legend

One.

“That… can’t be right”, I said – stunned and probably tripping over my words a little.

The departmental secretary shot me the look. The one all functionaries give when their authority is questioned, even in small ways.

Without looking back at the paper in front of her, she repeated herself: “You’ve been assigned to Mr. Ricci’s studio. There’s a signup sheet on his door for lesson times. Anything else I can help you with?”

Most people don’t get to meet their childhood idols. I’d just found out I’d be spending an hour a week studying privately with one of mine.

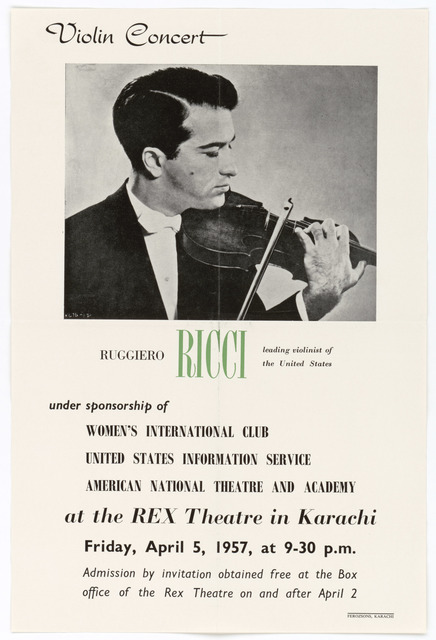

Ruggiero Ricci was one of the great violinists in history. A child prodigy, he made his debut concert at age 10 with the San Francisco Symphony, and went on to have a glittering career spanning the next 84 years – first as one of the busiest concert violinists, and after his semi-retirement from performing, devoting his remarkable energies to training the next several generations of violinists. This included several years teaching in the School of Music at the University of Michigan, which I had just entered as a freshman.

At one point, he held the distinction of having made the most recordings of any violinist – well over 500 (he still might hold that distinction, I just don’t know for sure). When I was growing up, it was impossible to listen to classical music programming on public radio without hearing one of his performances every month or so. As an 8-year-old just beginning to play violin, I went to the local library and checked out every recording of his that they had.

He reached the peak of his renown in the 1950’s and 1960’s. He’s probably less well-known today, but if you know the names of Hilary Hahn, Joshua Bell, or Itzhak Perlman now, you certainly would’ve known Ruggiero Ricci half a century ago.

For the next 2 years, I had a weekly one-on-one lesson with him. We also spent a good deal of time talking before and after – sometimes during – about our many shared interests and curiosities. I can’t really say we were friends – he was the world-renowned master and I was an 18-year-old kid, but we were certainly friendly, clicked well on a personal level, and found it easy to talk to each other.

He is the most accomplished person I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know well. I think it’s worth describing him – his character and abilities – and sharing a few good stories.

While there are many audio recordings of Ricci online, there are only a few good videos. To get a sense of his artistry, watch this video of him performing the last movement of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto – filmed in 1964 when he was at his very prime – and, I have a story about the violin he’s playing in this video:

Two.

You might assume that having such an exceptional teacher as Ruggiero Ricci meant that I was an exceptional violinist myself.

That’s not really the case.

I had all the raw ingredients to be a professional violinist, except one – burning desire.

You see, I had just entered University of Michigan as a composition major. It was where 95% of my interest lay, and it was where 95% of my energy went. We all had a requirement to study performance on our primary instrument as well, regardless of our major. On one level, I was just checking off that box so I could get on with my real work.

That was why I was so shocked when I got assigned to Ricci’s studio. There were 4 other violin professors in the music school, plus a host of qualified graduate students who also taught. I simply assumed I would be assigned to one of them.

Ricci was the superstar, and he got all the best students – plus a few like myself. He always understood my situation and was very gracious about it. I wasn’t held to the same standards as his real students, because I wasn’t there to practice violin 4 to 6 hours a day.

And what a superstar he was.

Some violinists are known for their lyrical tone. Others for the depth of feeling they bring to the music. Ricci had all of those things, but he was primarily known for his extraordinary technical abilities.

It was breathtaking to watch him play. His fingers at times seemed to defy the laws of physics and physiology.

He was the foremost performer of the works of Niccolo Paganini – the 19th century virtuoso and composer. Paganini was so extraordinary that he was rumored during his lifetime to have sold his soul to the Devil in return for his prowess on the instrument.

And Paganini’s compositions are devilishly difficult. They strain the boundaries of what is technically possible to be played – both on the instrument itself and for human hands.

When most violinists play Paganini, it just sounds labored and difficult – you can tell that the performer is at the very limit of their skill.

It was never like that when Ricci played Paganini. He made the pyrotechnics seem easy. And graceful. Even fun.

Once he was reclined in his office chair at about a 60 degree angle, with the scroll of his violin resting on his leg – about the worst possible posture for a violinist. Yet even in that position he shot off some fireworks that were so amazing I could only laugh in response.

And his memory was phenomenal. He knew the entire standard violin repertory by memory – maybe 50 or 60 long, difficult, taxing concertos, plus likely hundreds of solo and chamber pieces.

He told me that if he knew he was going to play the Beethoven Violin Concerto the next week, he would only practice technical exercises to get ready. He wouldn’t practice the concerto at all – he didn’t need to. He had known every note by heart since he was a child.

Once I brought in one of my own compositions for violin to show him. The next week he played it back for me – having only seen it once.

Here’s a short audio recording of Ricci playing some of Paganini’s solo violin music. It gives a pretty good idea of just how phenomenal his skill was:

Three.

At least a few of his students called him Yoda – not to his face, of course.

Far from being disrespectful, it was a fairly apt comparison.

Ruggiero Ricci was a physically small man – I stand 5’7″, and he was several inches shorter than me.

He spoke in a slightly unusual way – His parents were Italian immigrants, and he had the lilt, inflection, and sometimes curious grammar that you often find in first-generation English speakers who mostly heard their native language growing up at home.

And… he was a universally acknowledged master with commanding authority and preternatural abilities.

I was petrified going in to my first lesson with him. But, I was immediately set at ease by his simple ways and unpretentious – even humble – personality.

His most striking physical characteristic was his eyes – large, dark, searching eyes that peered directly into you – through you. It would have been an unnerving experience if they didn’t speak of a deep, gentle kindness and a profoundly humane understanding.

Mercifully, he was not an intellectual, with the rancor and combativeness that usually implies. Instead, he was gifted with a deep and wide-ranging curiosity. He had an open and flexible mind about nearly everything, as far as I could tell.

He did read, but I only ever saw him with one book. That’s not all that unusual, since most of us don’t bring our books to the office. But, one week he had on his desk a copy of Communion by Whitley Streiber – the book that launched the interest in the alien abduction phenomenon of the 1990s (Ricci said he was skeptical but interested). The cover of that book is the image we all know – the gray alien with the black insect eyes. And that cover image was painted by none other than Ted Seth Jacobs – the artist who trained many of the best realist painters working today. In fact, he taught my own teacher, and I was to meet him on a number of occasions.

At any rate, one week Ricci had assigned me a ferociously difficult piece to work on – one of the Paganini caprices. At the beginning of the hour, I played it – butchered it – and he simply told me to work on it some more. This suited us both just fine that day, since I didn’t have to play, and he didn’t have to listen.

We then spent the next 45 minutes talking about the collapse sequence that large stars go through immediately before becoming supernovas. This was all at my fingertips, since I was taking an astronomy class that term. I even wrote out a detailed diagram on his chalkboard of what happens in the last few seconds of the collapse and subsequent explosion. I’m sure the markings about radiation pressure and a fused nickel-iron core puzzled the next few students after me.

He was very engaged in the conversation, asked all the right questions – a lot of them – and told me he was deeply interested in the topic and had known a number of physicists during his life.

Many years later, I would find out that this was true in spectacular fashion.

Here is a touching video of Ricci late in life – recorded at his 91st birthday celebration in 2009. Although the recording quality isn’t the best, his warmth and humor are readily apparent:

Four.

“That one… play it”, he said, jutting his chin to indicate a violin sitting in an open case.

Ruggiero Ricci owned a large collection of violins… about 20 of them. It seemed like he had a different instrument with him every week. From time to time, he would have me play one, and we would then talk about it, just like he was having me do that day.

I picked it up, and played a few lines of Bach on it. I gave a facial shrug, and replied “I don’t like it… it isn’t very good”.

He gave a surprised chuckle, and told me to look inside. I went cold all over when I read the label, and felt a knot in the pit of my stomach. He laughed even harder at my obvious mortification.

I was holding his primary concert instrument – no mere Stradivari, but a Del Gesu, made in 1731 and worth millions of dollars.

Guiseppe Guarneri “Del Gesu” was Stradivari’s contemporary – neighbor, in fact. He’s the only maker who is generally thought to rival Stradivari. The labels on his instruments bear a stylized cross, so he is commonly called “Del Gesu” – Italian for “Of Jesus”.

Stradivari was the Golden Boy who had it all – rich, famous, and living well into his 90s. By contrast, Del Gesu had a rough life – and short – and he apparently struggled with his craft. He certainly never got rich.

And yet…

While violins made by Stradivari are prized for their clarity and sweet tone, Del Gesus are all about strength and power. There’s a raw force and energy about his creations, and in the hands of the right violinist, they can have a wild – almost demonic – fire to them.

And they are rare. While about 1600 instruments by Stradivari survive, fewer than 200 Del Gesus have come down to us. Because of that, they’re generally more expensive at auction than Stradivaris. And violinists love them. Those who know, often enough prefer a Del Gesu.

And I had just belittled one right to its owner’s face.

Once Ricci got over his amusement at my expense, he told me to play it some more. These old instruments are like people – they take a while to get to know, and don’t divulge all their secrets right away.

After a few minutes, I started to learn how to get The Sound from it, and it was glorious. 30 years later, I can still vividly feel how my entire body merged into the thrilling power of that exquisite violin.

Below is a recording of Ricci playing the Sibelius Violin Concerto. It gives a real sense of the depth and power of the Del Gesu.

Five.

Ruggiero Ricci had the air of an urbane mid-century gentleman about him. There was also something buoyant and joyful about his personality. He was animated, cheerful, and lively when he talked, and sometimes seemed barely able to contain his energy. He seemed like he was always enjoying himself.

His success afforded him a comfortable lifestyle, and presented himself in a refined but understated way. In particular, he had a collection of fine wrist watches, which we would sometimes talk about. He was especially proud of his Patek Philippe – a truly beautiful watch.

Once during in my freshman year I went with a group of friends to New York City for the weekend, and I bought myself a fake Rolex.

At the start of my next lesson after returning, I took the watch off and set it in my violin case just like I always did – violinists often choose to not wear watches while playing so as not to constrain the wrist in any way.

After playing for a few minutes, I noticed he was standing in front of the case, poking at the watch with his (very expensive) violin bow.

I stopped playing.

“This new?” he asked.

“Yeah. I got it this weekend.”

“Mmm. Is it real?”

“Of course not.”

He picked it up and looked closely with his experienced eye. “Ah. No. Of course not”, he repeated. “Where’d you get it?”

“Street corner in New York”

“Heh. How much you pay for it?”

“50 bucks”

“DAMMIT” he barked. “I just paid 75 for a fake in Hong Kong.”

I found it part of his charm that the man who owned several real Rolexes also owned a fake one.

Below is a recording of Ricci playing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto.

Six.

I read the thin, delicate handwriting, and I just couldn’t believe what it said.

I read it again… and again… and again.

It was the late 90s – I don’t remember the exact year. I was at the Museum of Science in Boston, viewing an exhibit about the life of Einstein.

The friends I went there with were mostly science and engineering types, who were interested in Einstein for the obvious reasons.

I was interested for a different reason. Decades earlier, when I was 8, I had read a biography of Einstein – maybe in the encyclopedia – I don’t remember where – and it mentioned that he was a enthusiastic amateur violinist.

Something about the clicked for me, and I decided that I wanted to play too. And so music became the focus of my life for many years after that. Among other things, reading about Einstein playing violin led me to studying the instrument with Ruggiero Ricci – one of the greatest violinists.

My friends and I walked slowly through the rooms of the exhibit – it was crowded. While my friends were looking at the scientific aspects of his life, I was mostly interested in the musical side of his life. The exhibit had one photograph of Einstein playing violin, and a few paragraphs of text explaining his life-long interest.

But there wasn’t much else – I was ready to leave slightly disappointed.

And then I saw it.

In the middle of the final room of the exhibit was a small glass display case with one small book in it – the guest book from Einstein’s vacation home. It was open to a page with several entries, but the largest entry – with the delicate handwriting – thanked Einstein for the wonderful weekend of music making and fascinating conversation.

Signed, Ruggiero Ricci.

Even though Ricci often spoke about some of the prominent people he had known, and even though we talked about the sciences – and physics in particular – on a few occasions, he never mentioned to me that he knew Einstein personally… just that he had known physicists.

It was just one of those beautiful little webs of connections and coincidences the Universe gives us from time to time.

Ruggiero Ricci passed in 2012, at the age of 94.

He was admired and respected by music lovers across the globe, and he was beloved by generations of students, whose careers he nurtured and guided.

My own life has certainly been richer for having known him.